|

Figure One - From left to right: the distal end of a fossilized mammalian tibia and two

fossilized mandibles with alveoli (bony sockets) with partial teeth.

Species are unknown. For scale, the tibia is 4.3 inches long.

|

In this article, I will briefly discuss a fossilization process called permineralization and show four examples of the process found in the field. The Dictionary of Geological Terms by Robert L. Bates and Julia A. Jackson defines permineralization as the process of fossilization wherein the original hard parts of an animal have additional mineral matter deposited in their pore spaces.

Figure one is a photograph of three fossilized mammal bones that I surface found in the sand of a dry creek in northern Colorado on 12/6/2022. On the left, is the distal end of a mammal tibia and on the right are two mammal mandibles showing the alveoli with a few broken teeth remaining within. Although these fossils were surface finds and I found them out of their original geological context, I am guessing they are from the Oligocene geological epoch since that was the rock outcrops that surrounded the dry creek. If they came from the fossil record of the Oligocene, that would put the mammals that left the fossils behind in an age group between thirty-four to twenty-three million years old.

When an organism dies in nature its remains usually follow the “dust to dust” routine and slowly disintegrate into the soil. Organisms are rarely preserved intact for the fossil record. If Mother Nature preserves any portion of an animal or tree, it is usually the hard body parts like bone, wood, or shell. For those durable body parts to become fossilized, a quick burial must happen to protect them from further decay and destruction. Once buried, soil conditions and groundwater determine the survivability of the rest of the remains.

|

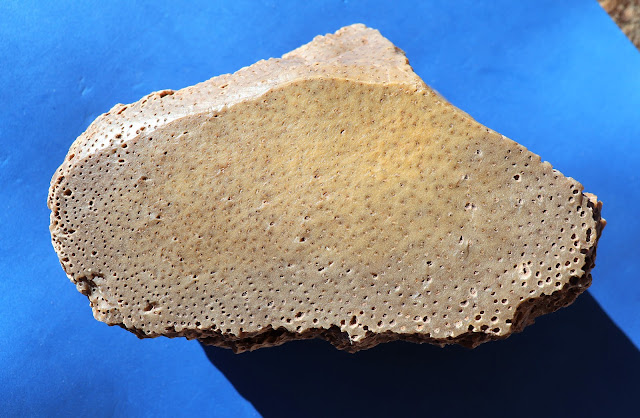

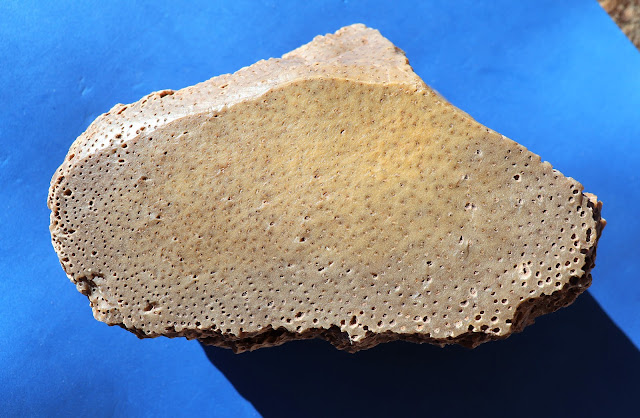

Figure Two - A slab of silicified palm wood or Palmoxylon, surface found by the author

in Washington County, Texas around the year 2012. Note the orientation of

the thin tubes. The scale is 6.3 inches long for the slab. |

Anyone who has lived in an area with untreated ‘hard water’ knows what their pipes and plumbing fixtures look like after a few years. Those people witness the evidence that groundwater is not pure H₂O. There are other minerals in the water. As water moves through the ground, it dissolves organic matter from the soil, making the liquid slightly acidic. Rainwater that permeates the soil and recharges aquifers carries CO₂ with it from the atmosphere

and becomes a weak carbonic acid or H₂CO₃. As that acidic water moves through the ground, it is corrosive enough to dissolve minerals such as calcite, silica, and iron from the surrounding soil

and bedrock.

|

Figure Three - Same Palmoxylon slab as in figure two, looking straight down at the rodlike

structures that parallel the original axis of the trunk of the palm tree.

The slab is 6.3 inches long. |

Figures two and three are photographs of a piece of fossilized palm wood or Palmoxylon that I surface found in Washington County, Texas, sometime around the year 2012. Palmoxylon is the state rock of Texas and it is an extinct genus of palm trees that grew from the late Cretaceous to the early Miocene (eighty-three to eleven million years ago). The thin tubes or rodlike structures in figure three parallel the original orientation of the trunk of the palm tree. For permineralization or silicification to have occurred in this example, the original wood cell walls were permeable to groundwater flow and the tree decayed slowly enough to allow silicate minerals in the groundwater to replace the original woody structure.

|

Figure Four - Fossilized skull from an unknown mammal

species found in a dry creek bed on 12/6/2022.

The skull is 3.7 inches long. |

For the process of permineralization to work, the original material must be porous and permeable. Bones, wood, and shells may look solid, but they contain minute

voids and pore spaces. Mineralized water advances through the soil and penetrates the pores spaces of the original material. When the water evaporates, the minerals drop out of the solution and remain in the pore spaces. Over hundreds or thousands or millions of years, the process repeats itself and creates layers upon

layers of mineral deposits in the pores and voids of the original bone, wood, or

shell. The minerals preserve the original shape and integrity of the host and prevent

tissue compaction. The permineralization

process literally turns bone or wood or shell into rock.

|

Figure Five - More permineralization examples of mammalian mandibles that I

surface recovered from Oligocene and Miocene rock in northern Colorado.

The longest example is 2.1 inches long. Species are unknown.

The historical fiction novels written by John Bradford Branney are known for their impeccable research and biting realism. In his latest blockbuster novel Beyond the Campfire, Branney catapults his readers back into Prehistoric America where they reunite with some familiar faces from Branney’s best-selling prehistoric adventure series the Shadows on the Trail Pentalogy.

John Bradford Branney holds a geology degree from the University of Wyoming and an MBA from the University of Colorado. John lives in the Colorado mountains with his wife, Theresa. |

No comments:

Post a Comment