My prehistoric adventure series titled

the SHADOWS

ON THE TRAIL QUADRILOGY took place around 10,700 years ago in what we now call Texas and Colorado. The SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL QUADRILOGY is about

the challenging survival of a group of Paleoindian hunters and gatherers called

the Folsom People. What makes the SHADOWS

ON THE TRAIL QUADRILOGY different from your ordinary fictional adventure is that the Folsom People actually existed in North America’s prehistoric

past. How do we know the Folsom People existed? Easy, they left behind a very

distinct calling card, a culturally diagnostic stone projectile point that was named Folsom for the place it was first documented; Folsom, New Mexico.

|

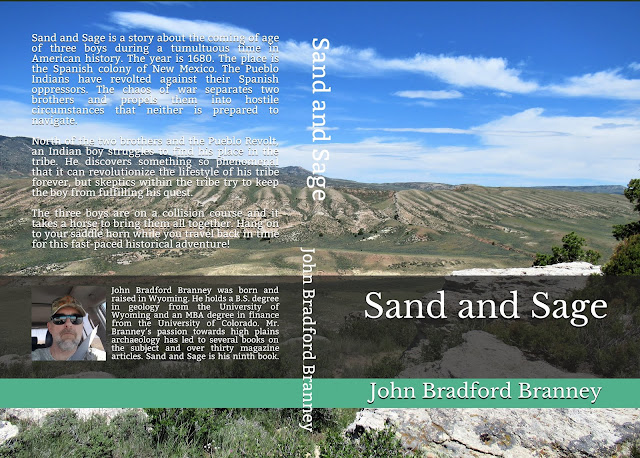

| FIGURE TWO. Click for SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL |

Folsom points (Figure one) are thin, small to medium size, well-made projectile points with convex sides, a concave basal edge, sharp basal corners and ground stem edges. What makes Folsom projectile points distinctive from other prehistoric stone projectile point types? Besides the remarkable workmanship, the most distinctive characteristic of Folsom projectile points are the flutes or channels that run most of the length up the middle of the projectile point, starting at the base. The knapping skill required to create flutes on a Folsom projectile point is without equal in America’s prehistory. Even modern day knapping experts are challenged in making replica Folsom projectile points using the same tools and materials that were available to Folsom People in the Pleistocene.

When the Folsom People created these thin, fluted, projectile points, they not only created an important component in their weaponry, but they also created works of art. Folsom projectile points are arguably the finest projectile points ever made in North America. No one has yet confirmed the exact manufacturing process that Folsom People used to make these fluted projectile points. This is not to say that people do not have their pet theories. In fact, you can add me to that list of having a pet theory on how Folsom People made their projectile points.

In the first book of the QUADRILOGY titled SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL, I wrote about the

|

FIGURE THREE. Folsom point surface found on

private land in Natrona County, Wyoming.

John Branney Collection.

|

In the scene below from SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL, a young Folsom hunter named Chayton was learning how to make fluted projectile points from Tarca Sapa, a salty old tribal healer. In this scene Chayton shows up and wants Tarca Sapa to tutor him on the finer points of making fluted projectile points.

“I have spear

points for our journey, but I need you to help me flute them,” Chayton

requested.

“I have shown you

how to flute before. Why have you not learned what I have taught you?”

“I do not want to

ruin these spear points since we leave the canyon tomorrow.”

“Do you think I

have nothing better to do than to teach you something I have already taught

you?” Tarca Sapa queried. “I will watch you flute only one. The rest you must

do yourself.”

Chayton had

expected this reaction from Tarca Sapa. It was the old man’s way. Tarca Sapa

always complained, but always found the time to ensure Chayton learned

properly. Chayton handed Tarca Sapa the spear points, one at a time. Each spear

point was approximately the length of a finger and wider than a thumb. The tip

of each spear point was slightly rounded, but still dangerously sharp while the

base of the spear point, where the spear point attached to a wooden shaft, had

two sharp ears. In the middle of the spear point’s base, between the two ears,

Chayton had knapped a small square platform. When hit with an antler hammer

precisely in the right place, the rock would crack and a long thin flake would detach

from the middle of the spear point. A flute channel would remain where the long

thin flake detached. How well this square platform was

constructed and then struck with the antler hammer meant the difference between

a good spear point and a broken spear point.

The platform was where Tarca Sapa focused his eyes. Tarca Sapa looked at each spear point carefully and put each inspected spear point in one of two piles. Once his inspection was over, Tarca Sapa touched the pile with seven spear points and said, “These points are good, the others need work. Now, let me see you drive a flute channel into the spear point.”

With his hands

shaking, Chayton opened up his leather pouch and pulled out two thick pads made

from buffalo hide and two elk antler hammers. He sat down on a nearby rock and

covered his legs with the thick pads. He placed a spear point, tip down, along the

inside of his left thigh and then placed an elk antler hammer horizontally on

top of the platform at the base of the projectile point. He braced the other

end of the elk antler hammer against the inside of his right thigh. When

Chayton had the hammer precisely lined up with the small square platform, he

took the second elk antler hammer in his right hand and swung down hard on top

of the first elk hammer. Nothing happened.

Flustered, Chayton

looked over at Tonkala hoping that she was not watching. Chayton then looked at

Tarca Sapa hoping for some words of encouragement, but Tarca Sapa only stared

straight ahead at the spear point still resting in Chayton’s lap. Chayton

nervously lined up the spear point, this time swinging the hammer even harder,

striking the spear point with much more force. A solid cracking sound came from

the spear point and Chayton looked down and saw the long thin flake that had

detached from the spear point. To Chayton’s delight, the spear point had a

beautiful flute channel running its entire length.

"It looks like you

don’t need me after all.” Tarca Sapa said with a smile. “Take the rest of the

spear points and finish them.”

|

| FIGURE FOUR. 2.5 inch long Folsom preform certified by Greg Perino*. John Branney Collection. |

|

| FIGURE FIVE. Striking platform to create flute on projectile point. |

|

| FIGURE SIX. Rounded and beveled tip of projectile point. |

The fluted points that Chayton took to Tarca Sapa were not finished and looked like the unfinished Folsom preform projectile point in FIGURE FOUR. An anonymous collector found this Folsom preform projectile point in Mecosta County, Michigan. The material is Norwood Chert. This particular preform was ready for fluting. The Paleoindian knapper had pressure flaked both faces of the preform leaving closely spaced flakes terminating near the middle of the biface. He or she rounded, beveled and abraded the distal end or tip of the preform which aided the fluting process (FIGURE SIX).

To assist the flutes, the Paleoindian knapper isolated a striking platform in the center portion of the projectile point base or proximal end.

The Paleoindian knapper accomplished this by creating a small nipple or striking platform in the center of the preform base (FIGURE FIVE). Then, he or she removed two pressure

flakes from either side of the striking platform so that the maker’s antler

punch could reach the striking platform without interference from the rest of the point. The Paleoindian knapper stabilized the striking platform or nipple by beveling, grinding, and polishing it.

This Folsom preform would have made Tarca Sapa very happy! Read the SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL QUADRILOGY for all the stories!