|

| Figure one - The 1.6-inch-long Lookingbill dart point I found on July 9, 2015

at the SHADOWS on the TRAIL Site.

|

|

On an overcast and rainy July 9, 2015, I returned to the SHADOWS on the TRAIL Site in northern Colorado for a visit. At the time we were living in Houston, Texas. A building contractor was constructing our new home in the Colorado mountains and we were in town to check on his progress. I took the day off and instead of bugging the building contractor, I went artifact hunting at one of my favorite sites. Following is my story about the SHADOWS on the TRAIL Site.

In the early 1980s, I discovered a copy of a master's thesis written in the 1960s about northeastern Colorado archaeology. The anthropology student visited several dozen archaeological sites in northern Colorado and then wrote about them. If I remember right, the grad student never discovered any of the sites himself but relied on information from old documents from archaeologists like E.B. Renaud (1931) or from word of mouth with local collectors or landowners. The master's candidate mostly surface-hunted the sites, although I do remember that he dug a couple of test trenches on a site or two. I studied that thesis from beginning to end and based on the locations described, I investigated most of the sites myself.

I was mostly disappointed with the results of my master's thesis project. Local collectors knew about most of the sites and were hunting them for decades. However, there was one site, a possible jewel off the beaten path. The thesis barely mentioned that site, devoting less than one page to it. Thirty years and some change later I named that site SHADOWS on the TRAIL.

|

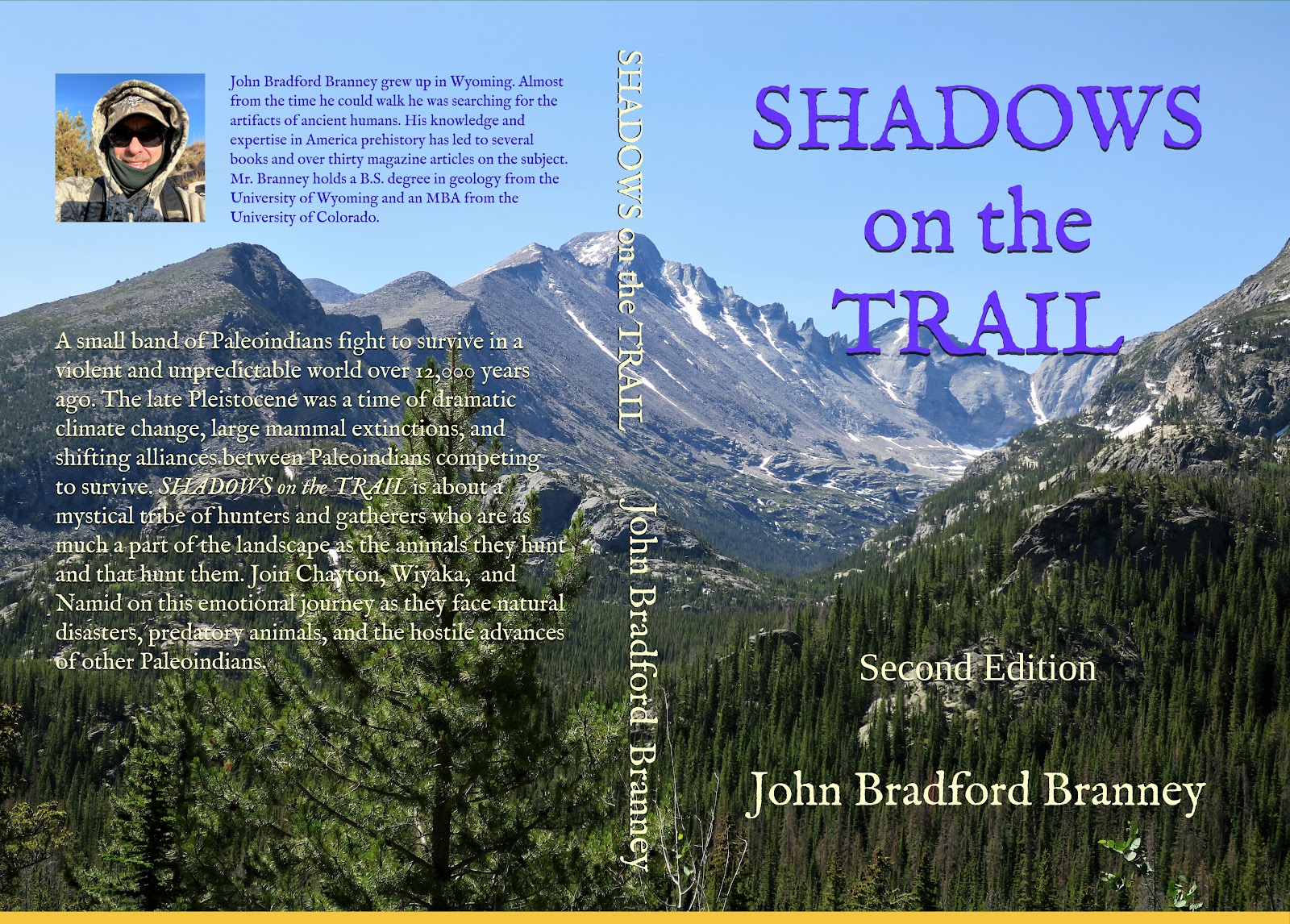

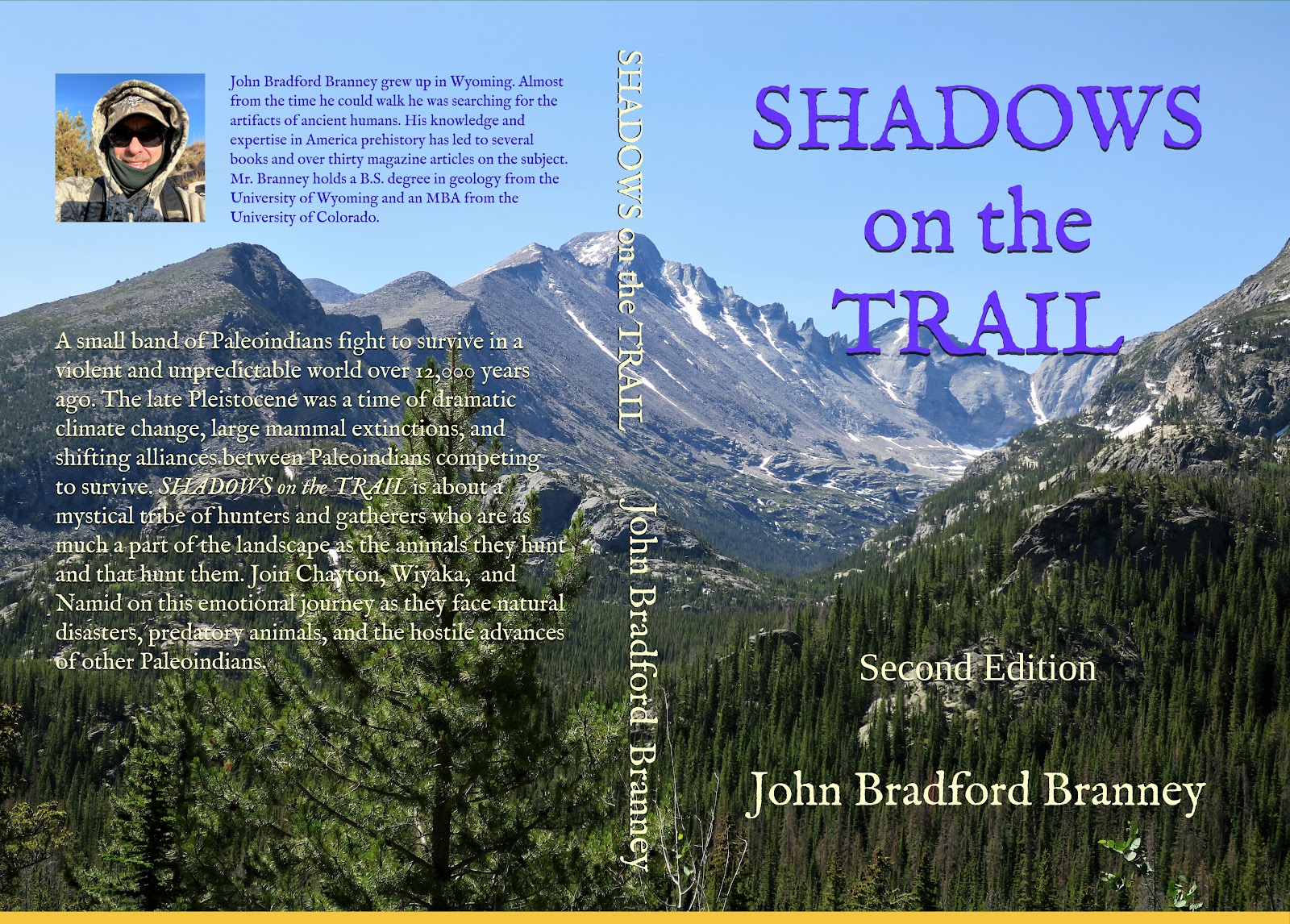

Figure Two - The first book in my historical fiction series

about the Folsom People. |

On December 20, 1986, I made my first trip to the ranch where the site was. The road was not much better than a rutted Jeep trail. Back then, I was driving a front-wheel drive car with little ground clearance. I slowly drove on that glorified cow trail for about five miles never knowing when or where I might hit something hard enough to rip my car's oil pan off. About two hundred yards away from the tiny ranch house, the road crossed a dry creek bed filled with sand. I punched the accelerator and the vehicle slid across the top of that sand like a toboggan on snow. I felt very fortunate that I made it through the sandy creek bottom without high-centering my low-slung vehicle in the sand. I concluded from the condition of the road that the ranchers didn't make it to town too often. When I reached the ranch house, another surprise awaited me. The ranchers owned a humongous St. Bernard dog, and when it saw my car coming, it bolted off the front porch to greet me and my vehicle. The dog was tall enough to stand there on all fours and peer right into my driver's side window. Anyone who has ever been around St. Bernard dogs knows that they are world-class slobberers. That gigantic beast 'slimed' my car window from one end to the other with a mixture of gooey dog slobber and mud.

Needless to say, I did not even try to get out of the car. Remember, the year was 1986, a few years after the horror book and movie titled Cujo came out. In the book, Cujo was a St. Bernard dog that was crazy nuts with rabies and trapped a young boy in a car. I won't tell you how the book ended, but it didn't end well for the boy or the beast. I wondered if that St. Bernard at my car window happened to be a relative of Cujo.

The rancher's wife heard Cujo carrying on and she called the dog off. I was relieved that the beast did not eat my entire car for breakfast. Once I received permission to hunt artifacts, I headed off to the hills with Cujo tagging along behind. The dog stayed with me for about half the day and then became bored and headed back to the ranch house. On that first hunt, I didn't do that great, finding only three broken artifacts. However, there was a positive note to the hunt; I did find a bunch of chipping debris. Early humans were definitely there! I left the ranch thinking that the site deserved another look.

|

Figure Three - Prehistoric fire hearth eroding from an embankment at the SHADOWS on the

TRAIL Site. The photograph was taken by the author on July 9, 2015.

|

Since that first visit to the ranch, I have watched the ranch change hands four times. My artifact hunting has somehow survived five different ranch owners, which is a modern miracle in itself knowing how getting access to large ranches has plummeted in recent years. Over that same period, I have found hundreds of artifacts on the site from early Paleoindian to the historical Indian tribes. I have found a dozen or so different diagnostic projectile point types representing different archaeological complexes. The site was occupied by various prehistoric cultures from over 13,000 years ago until the European settlers showed up in the 1800s.

|

Figure Four - The cutbank where I found the 1.6-inch-long Lookingbill dart point

on July 9, 2015. Site in northern Colorado. The red arrow marks the spot.

|

When I returned to SHADOWS on the TRAIL on July 9, 2015, the site did not disappoint me. One of the first artifacts that I found was the 1.6-inch-long Lookingbill dart point photographed in Figures one and five. Lookingbill dart points were made around 7,000 years ago. Dr.

George C. Frison named Lookingbill points for a point type found in

northwestern Wyoming (Frison 1983). Frison classified the Lookingbill points as Early Plains

Archaic. Lookingbill points were one of the first point types on the High Plains of

the Rocky Mountain states to be found in appreciable numbers associated with manos

and metates.

|

| Figure Five - 1.6-inch-long Lookingbill dart point as I found it on July 9, 2015. |

Lookingbill points were thin, small to medium-sized dart points with triangular blades and side

notching. The shoulders were sharp and angular and the notches were rounded and sometimes

close to the basal edge. The shapes of the bases ranged from straight to slightly concave. The

Lookingbill point I found exhibited heavy grinding and polishing along the basal edge,

accounting for a bit of its basal concavity.

On that July 9, 2015 artifact hunt, I found twenty-four prehistoric artifacts including the Lookingbill projectile point.

|

Figure Six - My hunting companion for about five feet or fifteen seconds on July 9, 2015.

Horned toad claws are like sharp needles and that little guy was hanging on

to my thumb and finger for dear life. |

Several years before finding the Lookingbill point, on August 30, 2007, I found a 1.36-inch-long Folsom dart point/knife form stuck in the clay-packed soil in an embankment on the ranch. When I spotted the tiny sliver of Flattop Chalcedony sticking out of the soil bank, I didn't have a clue it was an artifact. When I washed away the dirt clod surrounding it, I realized I found a Folsom point, the rarest of the rare! I was shocked, to say the least! (Figure seven).

That Folsom point was part of my inspiration behind writing my historical fiction book series about the Folsom People and that particular site titled SHADOWS on the TRAIL Pentalogy.

|

Figure Seven - 1.36-inch-long semi-translucent Folsom point posing for a photograph after

I washed the dirt off it. The embankment where it was found is behind the point. |

The true seed for my book series sprouted on a late Spring morning in 2010 at the ranch when I found a Paleoindian tool made from a red and gray striped

rock from a prehistoric rock quarry in Texas (figure eight). As I stared down at a discoidal biface made by one of our First Americans, several questions raced

through my mind. How did this tool end up in a prehistoric campsite in northern

Colorado, five hundred miles north of its prehistoric rock quarry? Who

made it? What was he or she like? What happened on its journey from Texas to

northern Colorado? Since it was impossible to ask the Paleoindian

who made that stone tool those questions, I wrote my own version of its journey from prehistoric Texas to Colorado.

|

Figure Eight - 4.1-inch-long discoidal biface made from Alibates agatized dolomite and

found on May 30, 2010. This artifact was the main inspiration for my book series

SHADOWS on the TRAIL Pentalogy. |

Over the years I added more and more artifacts to my collection from the SHADOWS on the TRAIL Site, but artifact finds were becoming fewer and farther between. I was relying on erosion to keep up with my hunting pressure and it wasn't. On June 5, 2020, I surface recovered a 1.9-inch-long Scottsbluff dart point from the Cody Complex in a dry stream bed on the west side of the SHADOWS on the TRAIL Site (figure nine). That projectile point was the eighth Scottsbluff dart point/knife form that I have found on the site since 1986.

|

Figure Nine - 1.9-inch-long Scottsbluff point that I found lying on top of

the sand in 2020. Of all the Paleoindian points I have found at the site,

Cody Complex and Goshen artifacts are the most common rarities. |

Rains ended a dry spell for Paleoindian artifacts from 2020 to 2023. On May 23, 2023, I discovered a 1.4-inch-long Midland or Goshen point eroding from an embankment (Figure ten). I am not sure whether that point is a Midland or a Goshen point. If it was a Midland point, it was the third diagnostic Midland artifact that I found at the site. I previously found two Midland projectile point bases on two separate occasions. If it was a Goshen point, it would be the tenth diagnostic Goshen artifact from the site.

|

Figure Ten - 1.4-inch-long, very thin Midland point

found May 27, 2023. |

Goshen and Midland projectile points are very similar and when they are surface found out of their archaeological context, it is difficult to impossible to distinguish between them. The two projectile point types have more in common than they have differences. The criteria that I use to distinguish Goshen from Midland points found on the surface of the ground are 1). the aggressive basal thinning strikes on Goshen projectile points and 2). Midland points were flat and oftentimes bore fine pressure retouching around a good deal of the circumference of the point. Even those criteria are not conclusive. For example, the thin Midland projectile point in Figure ten has basal thinning strikes on one face. Is it a Goshen point or a Midland point, or does it really matter? For the answer to that last question, I refer you to Branney (2022).

The Hell Gap site in eastern Wyoming is unparalleled in North America for its continuous record of Paleoindian deposits. Bruce Bradley (2009:259-262) in his analysis of bifacial technology at the Hell Gap site pondered the relationship between Goshen-Folsom-Midland. Over the years, Bradley was involved in the Folsom-Midland debate and later in the Goshen-Plainview debate. At the Hell Gap site, Bradley was attempting to determine the cultural and technological relationship between Folsom and Midland, and Goshen and Plainview.

Bradley struggled with determining tangible differences between Midland and Goshen and never came up with any definitive answers. He analyzed eight projectile points recovered from the Midland component at Hell Gap and identified one point as Folsom, two points as Goshen, one point as unclassified, and four points as Midland.

After that analysis, Bradley concluded, “As I look back at these classifications and reevaluate them in light of my confusion over the separation of the unfluted points, I am as unsure as ever that these categories are really meaningful. Nevertheless, I maintain my original classifications for those discussions.”

|

Figure Eleven - "G" was where I found the Midland point on May 27, 2023. "O" is an

organic layer that runs through the site. I believe it represents the deposits during

the Paleoindian occupation at the site. |

Every artifact hunter or archaeologist needs a site like SHADOWS on the TRAIL. For me, it is a place where I can fulfill my artifact dreams, or at least try. The land is so beautiful and I am sure that was one of the reasons prehistoric people periodically occupied the site for over 13,000 years. When I am walking that land, I really don't need to find artifacts to enjoy myself. Finding the occasional artifact is an added bonus to the site. I have been 'skunked' on the site a few times, but what keeps me coming back is wondering what incredible artifact is lying there and waiting for me to return.

References cited

2009 Bradley, Bruce A.

"Bifacial Technology and Paleoindian Projectile Points" in Hell Gap, a Stratified Paleoindian Campsite at the Edge of the Rockies. The University of Utah Press. Salt Lake.

2022 Branney, John Bradford

"Unwinding a Twister-Goshen-Plainview/Midland". Academia.

1983 Frison, George C.

"The Lookingbill Site, Wyoming 48FR308". Tibewa. 20:1-16.

1931 Renaud, E. B.

Archaeological Survey of Eastern Colorado, First Report. Archaeological Survey, Department of Anthropology, University of Denver.

About the Author

The

historical fiction novels written by John Bradford Branney are known for

their impeccable research and biting realism. In his latest blockbuster novel Beyond

the Campfire, Branney catapults his readers back into Prehistoric

America where they reunite with some familiar faces from Branney’s best-selling

prehistoric adventure series the Shadows on the Trail Pentalogy.

John Bradford Branney holds a geology

degree from the University of Wyoming and an MBA from the University of

Colorado. John lives in the Colorado mountains with his family. Beyond

the Campfire is the eleventh published book by Branney.