In figure one, I photographed four high plains projectile points from my collection: on the far left is a 2.45-inch long Agate Basin projectile point and on the right are three Hell Gap projectile points. Bradley (1991:382) proposed that the manufacturing process for Hell Gap projectile points was an outgrowth from a well-developed Agate Basin projectile point technology. He postulated that the production sequence was the same for both projectile point types; first, there was percussion thinning and shaping followed by pressure thinning and shaping. Bradley stated that the makers of Hell Gap projectile points just terminated their flintknapping process earlier than the makers of Agate Basin projectile points.

Fortuitous circumstances led to the discovery of the Hell Gap archaeological site in southeastern Wyoming. Since its discovery over sixty-some years ago, Hell Gap has become one of the most important archaeological discoveries in North America and the type site for the Hell Gap projectile point.

On May 22nd, 1958, James Duguid and his family were traveling north along a gravel road between Guernsey and Lusk, Wyoming along the eastern flank of the Hartsville Uplift. Along came one of those afternoon rain showers that temporarily flooded a low spot in the road. The flood waters forced the family to stop and allow the water on the road to drain. The family bided their time by walking and artifact hunting in the immediate area. Duguid discovered some interesting artifacts in an arroyo and promised himself that he would return the next day to finish the hunt (Duguid 2009:313-314).

Duguid and a friend returned to the site the next day and Duguid found a complete Agate Basin point along with a lot of flintkapping debris. He returned to the site with his father and another friend the very next day on May 24th. Duguid's father Otto discovered what appeared to be a Paleoindian projectile point eroding from a cutbank. That point was later determined to be a Hell Gap projectile point. Between his father's Hell Gap point and his Agate Basin point, Duguid recognized that they stumbled upon a very special place. However, he was hesitant to report the site to professional archaeologists because he knew that there were archaeologists who failed to report and document other excavated Paleoindian sites in the area. Duguid was worried that the same fate might befall his newly discovered secret.

|

| Figure Three - The Hell Gap Paleoindian site in the late 1960s. |

In the fall of 1958, James Duguid began working on his geology degree at the University of Wyoming. In the fall of 1959, Duguid reported the site to University of Wyoming anthropology professor George A. Agogino. The professor convinced Duguid to take him to the site to investigate it. Duguid and his father escorted Agogino to Hell Gap Valley and the rest was history, or in that case, prehistory.

Sixty-plus years later, archaeologists are still investigating the Hell Gap Site. Hell Gap remains one of the most important archaeological discoveries in the Western United States during the past one hundred years, and that came about because of an avocational archaeologist named James Duguid.

| |

|

Based on excavated bison kill sites, it appears that Hell Gap Paleoindians participated in large, well-organized communal hunts for meat acquisition, much like their Paleoindian predecessors. Figure five is a photograph of a few projectile points excavated in a bison bonebed at the Agate Basin site in eastern Wyoming (Frison and Stanford 1982:101). In that photograph, two of the projectile points (o and p) were classic Hell Gap projectile points with shouldering. Those Hell Gap points were excavated from the same bonebed and stratigraphic level as Agate Basin projectile points. In addition to those two Hell Gap points, there were other examples of Hell Gap points excavated from the Agate Basin bonebed which provided evidence of a relationship between the two point types. Based on the evidence, it seems likely that Paleoindians used Hell Gap points contemporaneously with Agate Basin points at the Agate Basin site.

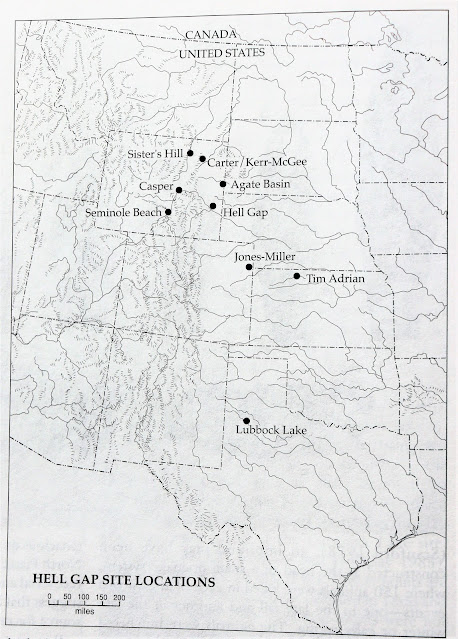

Stanford (1999:318) published the map in figure six of important Hell Gap sites along the High Plains. He noted that the number of Hell Gap sites was less than Cody and Folsom sites for the same area. Stanford made no assumptions or conclusions as to why there were fewer Hell Gap sites.

The Casper Site was originally discovered by avocational archaeologists. George Frison (1974) investigated the Casper Site in central Wyoming and determined it was a late-autumn bison kill site where Hell Gap Paleoindians harvested around one hundred animals by immobilizing them in the deep and shifting sands of a parabolic dune.

Using several Hell Gap point specimens from the Casper Site, Bradley (2010:487) proposed a special bifacial reduction process. He noted that Hell Gap flintknappers achieved the general shape and regularity of the biface by serial percussion thinning on one side with a hammerstone. In the world of flintknapping, serial percussion thinning usually results in the arrises, i.e. the high ridges at the flake margins, trending in the same direction. The Hell Gap flintknappers skillfully controlled the spacing and the thinning flakes that crossed the surface of the biface. Many of the thinning flakes reached or almost reached the other edge of the biface.

|

| Figure Seven - Clovis point and three Hell Gap projectile points from the Casper site (Frison 1974:74). |

The Hell Gap flintknappers then turned the bifaces over and percussion thinned from the opposite edge, creating bifaces with cross sections resembling a parallelogram. After serial percussion thinning, the Hell Gap flintknapper shaped and straightened the margins of the biface using direct percussion with an antler or hammerstone or by selective pressure flaking. Hell Gap flintknappers used platform isolation and moderate to heavy grinding to prepare the striking platforms for percussion flaking. Unlike Clovis striking platforms, Hell Gap flintknappers used smaller and more convex-shaped striking platforms. Bradley found in his study of the Hell Gap projectile points from the Casper site that a few flintknappers used percussion flaking exclusively while others chose to retouch the margin edges with pressure flakes, particularly near the tips and bases of the bifaces. Ultimately, the finished bifaces ended up with lens-shaped cross-sections. Figure seven represents the forms and flaking patterns of one Clovis and three Hell Gap projectile points found at the Casper Site.

Cassells (1997:79) reported that in the summer of 1972, rancher Robert Jones Jr. uncovered bones and artifacts while leveling a ridge near his home near Wray, Colorado. Jones contacted a local anthropologist named Jack Miller who conducted a few test excavations in the bonebed. Miller recognized the significance of the site and contacted archaeologist Dennis Stanford at the Smithsonian Institute. Full-scale excavations at the Jones-Miller site occurred between 1973 and 1978.

|

| Figure Eight - CLICK for SHADOWS on the TRAIL |

The Jones-Miller investigations uncovered the bones of approximately three hundred bison in a shallow arroyo above the Arikeree River floodplain. Based on bison tooth eruption patterns, the investigators determined that the animals were most likely killed during three episodes over one or more winters. The projectile points that the investigators found were mostly of the Hell Gap variety. Taylor (2006:207) reported and photographed what appeared to be Agate Basin points found with the Hell Gap points from a single kill episode at Jones-Miller. That either meant that Agate Basin and Hell Gap hunters were cooperating at that bison kill, or the mixture of point types represented the same complex using two different styles of points. In my opinion, the situation at Jones-Miller was most likely the latter.

Stanford (1999:316-318) observed that during the refurbishment or resharpening of Hell Gap points, the flintknappers could narrow the blade edge enough to make the points indistinguishable from Agate Basin points. Peck (2011:55) lumped Agate Basin and Hell Gap into the same archaeological complex based on the overlapping projectile point technology and the association between the two-point types at several archaeological sites such as Agate Basin, Carter-Kerr McGee, and Jones-Miller. Peck reported an age of ca. 10,500 to 10,000 BP for Agate Basin materials and an age of ca. 10,000 to 9,500 BP for Hell Gap materials at the Hell Gap Site in Wyoming (Irwin-Williams et al. 1973:52). To obtain the age of the materials in calendar years, the radiocarbon ages must be corrected.

Based on the archaeological evidence at Jones-Miller, the investigators proposed that Paleoindians trapped the bison in a topographical trough. The investigators found evidence that the Paleoindians might have used an enclosure or corral around the trough. Since the bison harvest took place in the wintertime, the investigators hypothesized that the entrance leading into the trough might have been slick with snow and ice, making it difficult for the beasts to escape. The hunters then trapped and dispatched the beasts with spears and possibly spearthrowers. Jones-Miller remains the only excavated Hell Gap site in Colorado.

What happened to the Hell Gap projectile point technology?

Figure nine is a photograph of four projectile points from my collection. These projectile points represent a plausible technological transition from the shouldering on the first two Hell Gap points on the left to the stemming on the two Alberta points from the Cody Complex on the right. The notion that Hell Gap projectile point technology evolved into Alberta projectile point technology is also supported from a temporal perspective. Kornfeld et. al. (2010:237) reported that the Alberta component at the Hudson Meng bison kill site in Nebraska was the approximate age as the Hell Gap component at the Casper bison kill site in central Wyoming. Both sites were dated to around 10,000 years BP (uncorrected radiocarbon date). While Hell Gap hunters were trapping bison in a parabolic sand dune in Wyoming, Alberta hunters were trapping bison in an ancient arroyo in Nebraska.

I hope you enjoyed the article. I am currently writing the sixth book in my SHADOWS on the TRAIL Hexalogy. Check out the series if you enjoy adventures about Paleoindians living on the High Plains.

Oh, I almost forgot about the projectile point types in figure four above. From left to right, the point types are Agate Basin, Hell Gap, Agate Basin, Hell Gap, and Agate Basin.

Until next time, HAPPY TRAILS!

References Cited.

Agogino, George A. 1961. A New Point Type from Hell Gap Valley, Eastern Wyoming. American Antiquity 26: 558-560, Salt Lake City.

Bradley, Bruce A. 1974. The Lithic Technology of the Casper Site Materials in The Casper Site: A Hell Gap Bison Kill on the High Plains, edited by George A. Frison. Academic Press. New York.

Bradley, Bruce A. 2009. Bifacial Technology and Paleoindian Projectile Points in Hell Gap: A Stratified Paleoindian Campsite at the Edge of the Rockies, edited by Mary Lou Larson, Marcel Kornfeld, and George C. Frison.

Bradley, Bruce A. 2010. Paleoindian Flaked Stone Technology on the Plains and in the Rockies in Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies. Third Edition. Edited by Marcel Kornfeld, George C. Frison, and Mary Lou Larson. Left Coast Press. Walnut Creek.

Cassell, E. Steve. 1997. The Archaeology of Colorado. Revised Edition. Johnson Books. Boulder.

Duguid, James O. 2009. A Paleoindian Site Discovery in Hell Gap: A Stratified Paleoindian Campsite at the Edge of the Rockies, edited by Mary Lou Larson, Marcel Kornfeld, and George C. Frison.

Frison, George A. 1974. The Casper Site: A Hell Gap Bison Kill on the High Plains. Academic Press. New York.

Frison, George C., and Dennis J. Stanford. 1982. The Agate Basin Site. Academic Press. New York.

Irwin-Williams, Cynthia, Henry Williams, George Agogino, and C. Vance Haynes. 1973. Hell Gap: Paleo-Indian Occupation on the High Plains. Plains Anthropologist. 18(59):40-53.

Peck, Trevor R. 2011. Light from Ancient Campfires. AU Press. Edmonton.

Stanford, Dennis. 1999. Paleoindian Archaeology and Late Pleistocene Environments in the Plains and Southwestern United States in Ice Age People of North America, edited by Robson Bonnichsen and Karen L. Turnmire. Oregon State University Press. Corvallis.

Taylor, Jeb. 2006. Projectile Points of the High Plains. Sheridan Books. Chelsea.

About the Author.

John Bradford Branney started collecting prehistoric artifacts in Wyoming with his family at the ripe old age of eight years old. He has amassed and documented a prehistoric artifact collection numbering in the thousands. He has written eleven historical fiction books and over ninety papers focused on Paleoindians, prehistoric artifacts, and geology. Branney holds a B.S. degree in geology from the University of Wyoming and an MBA in finance from the University of Colorado. He lives in the Colorado Mountains with his family.

No comments:

Post a Comment