|

| Figure One - The artifact cache. From TOP to BOTTOM: goose effigy, McKean Lanceolate point, and McKean Lanceolate point. |

I identified the two small projectile points as McKean Lanceolate from the Middle Archaic of Wyoming. Wheeler (1952) was the first to document and describe McKean Lanceolate points at the McKean-type site in Crook County, Wyoming. Wheeler and William Mulloy (1954) could not determine the age of human occupation at the type site, but a 1983 reinvestigation of the site yielded a date of around 4600 years BP (Kornfeld et al. 1995).

|

| Figure Two - High Plains McKean Lanceolate points. The two subject points of the article are on the bottom row, left. |

The two McKean Lanceolate points are small for the type. Figure two shows the two projectile points on the bottom row, left with other High Plains McKean Lanceolate points from my

collection. Since there is no scientific evidence that the bow and arrow weapon

system existed in North America as early as the Middle Archaic, I assume the two projectile points were used as darts in an atlatl weapon system, or as standalone spear

points.

The two McKean Lanceolate projectile points are similar in size, shape, and flaking patterns, and since they were found as a pair I surmise that the same individual made both points. The maker of the projectile points used high-quality raw materials: Wiggins Fork petrified wood for the projectile point on the left and Big Horn chert for the projectile point on the right. Both materials were sourced in northwestern Wyoming.

Both McKean Lanceolate projectile points were well crafted. That was atypical for McKean Lanceolate points during the Middle Archaic. The workmanship quality of projectile points dropped significantly from the Paleoindian and Early Archaic periods to the Middle Archaic period. Functionality became the main driver for Middle Archaic projectile points with aesthetics and craftsmanship becoming secondary. Workmanship quality is one way to differentiate McKean Lanceolate points from earlier Paleoindian and Early Archaic points on the High Plains. Another way is that Middle Archaic flintknappers rarely ground/polished the blade edges in the hafting area of the points while Paleoindian flintknappers did that much of the time.

Taylor (2006: 324) described McKean Lanceolate points as follows:

“McKean lanceolate points resemble earlier point types in outline, but they are morphologically and technologically quite different. Some were well made. However, most of them exhibit asymmetrical vertical cross sections and rather casually executed selective flaking.”

|

| Figure Three - Fly, birdie, fly. The waterfowl or goose effigy was found with two projectile points. Note wings and beak. |

Fagan (1987:73-77) reported that the

modern human species arrived in the Old World between 40,000 and

35,000 years ago, displacing or absorbing the Neanderthal population. According

to Fagan, modern humans introduced creativity and complexity into art forms. A few millennia after they arrived in Europe, modern humans developed an art culture and

inventory that included engravings, cave paintings, and other art. For

example, 25,000 years ago in the Czech Republic, modern humans were responsible

for creating the Venus figurines while humans were decorating mammoth bones and ivory with red ocher, and engraving human figures, animals, and geometric designs in Ukraine.

Why were animals so often used as artistic models by prehistoric humans? Cohen (2003:289) summarized it by stating that harmony with nature brought health and good fortune while disharmony with nature brought disease and famine. Prehistoric humans seemed abundantly clear about the delicate balance with nature. Their lives depended on it. If humans overhunted a certain animal species or location that could lead to bad consequences such as a disrupted food supply. There was no one to step in and help prehistoric humans if they depleted their food source. Prehistoric humans needed to understand nature and respect it. A way for prehistoric humans to demonstrate respect for nature was by honoring animals through rituals, prayer, and art forms.

|

| Figure Four - waterfowl effigy found in German cave. It is somewhere between 31,000 and 33,000 years old |

The earliest known representation of a bird in prehistoric art is currently an Upper Paleolithic waterfowl carved from mammoth ivory and found in two pieces in Hols Fels Cave in Germany (figure four). Scientists determined the age of the waterfowl effigy somewhere between 31,000 and 33,000 years old with a probable origin from an Early European modern human culture named Aurignacian. According to Conard (2003a:830), the handheld sculpture represented a water bird such as a diver, cormorant, or duck. The extended neck of the bird suggests the waterfowl model was in flight or diving in the water. Conard (2003b) stated that experts in shamanism believe birds, especially waterfowl, were favorite prehistoric shamanistic subjects and symbols. In an interview, Conard said, "Advocates of the shamanistic hypothesis are going to be very happy about these finds."

I found little information on handheld prehistoric bird effigies and figurines for the High Plains of North America. I attribute that to the scarcity of authentic prehistoric effigies. One-off artifacts like the goose effigy do not lend themselves to much study. Plus, there is an authentication issue with effigies and figurines in general. Touting modern reproduction animal effigies and figurines as prehistoric is unfortunately quite prolific.

Anyone who has visited a tourist shop in the western United States has probably seen examples of modern reproductions of prehistoric animal figurines and effigies. The shops might label them as reproductions or authentic, but in all cases, buyers beware. Examples include clay and flint-knapped thunderbirds, bears, and lizards sold to an unwary public. Modern reproductions are so prolific in the artifact world that my first inclination when I see one is to assume the item is fake.

|

| Figure Five - Bird effigy made from ruby red glass (Parman 1989:30) |

Figure five is a drawing of a modern reproduction of a bird effigy made from ruby red glass (Parman 1989:30). That

particular example was in Robert C. Parker’s collection in Casper, Wyoming. Its owner believed it to be an authentic Native American ceremonial piece. The piece originated

in the 1930s collection of Horace Evans who operated the tourist center at

Hell’s Half Acre west of Casper. While that bird effigy might be an early Twentieth-century antique, it is not prehistoric.

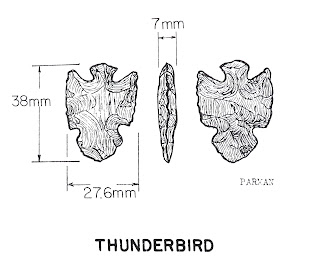

One of the more commonly replicated bird effigies is the thunderbird. Figure six is an example of a flint-knapped thunderbird with a stated provenance near Oregon Buttes in north central Sweetwater County, Wyoming (Parman 1989:17). That example was in the Alfred and Virginia Lindell of Lander, Wyoming collection. The big question is whether it is prehistoric or not. That cannot be determined from the drawing alone.

|

| Figure Six - Thunderbird effigy reportedly from the Red Desert of Wyoming (Parman1989:17) |

According to Warren (2007:124),

ethnographic accounts and archaeological evidence determined that the

thunderbird was a widespread component of Native American cultures. According

to the author, the thunderbird was a supernatural deity representing thunderstorms

and warfare to Native Americans. He reported that thunderbirds were prominent

in the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes living along the Missouri and Knife

rivers in the Dakotas. Warren surmised that those thunderbird effigies might have

originated in the eighth century AD from the Woodland cultures in the Midwest or an earlier Mississippian culture south of there.

Bear effigies are another prime target for reproduction by modern craftsmen. Whenever I see a flint knapped or clay bear effigy claiming to be prehistoric, my first inclination is fake. However, there is at least one authentic handheld bear effigy. Thomas (1994:61) reported on the grizzly bear effigy in figure seven. I must admit that when I first saw a photograph of that grizzly bear without knowing its history or provenance, I thought a modern-day flintknapper had fun making it. Archaeologists discovered the bear effigy in an archaeological site in San Diego County, California. They dated it at around 8,000 years old, and the people of California made that grizzly bear effigy their state artifact. We will never know why the grizzly bear's maker made it but the moral of that story is one cannot always judge an artifact by its first impression.

|

| Figure Seven - California State Artifact. (Thomas 1994:61) |

Steege and Welsh (1967:21) reported that the highest concentration of rare handheld effigies were from the Mississippi Valley and northeastern Oklahoma. The authors noted that eagles and turtles were the most popular designs but that there were also snakes, lizards, flying birds, and even human faces. Wedel (1978) added that animal effigies were more common on the east side of the Great Plains than on the west. He cited nineteenth-century archaeological sites in Kansas with small pottery figurines and the Spanish Fort site where archaeologists discovered clay fragments representing animals, humans, and a horse head with a carved bridle. Steege and Welsh noted that the authenticity of effigies was an issue.

Russell (1974:150) declared that stone

effigies were rare in the Rocky Mountain region and that the commonest animal effigy

was the eagle followed by lizards, turtles, trees, wild geese, and snakes.

Russell agreed that the authenticity of animal effigies was a big problem. Ironically,

Russell showed a drawing on page 147 of his book with an elaborately knapped

eagle and fishhook. I would bet my eyeteeth that the eagle was a modern

reproduction, and I have yet to see any flint-knapped fishhooks that I would call

authentic. Native Americans used bone for most fishhooks. The eagle and fishhook could be prehistoric, but modern reproductions of effigies and figurines raised the skepticism.

Of all the mighty predators and prey animals inhabiting the High Plains during the Middle Archaic, why would the prehistoric sculptor pick a goose or waterfowl as the model? In my research, I looked for other examples of geese or waterfowl in hand-held effigies from the High Plains. They might exist but are yet undocumented. I found a documented Hopewell duck effigy pipe from Ohio and part of the Museum of Native American History (2023) but that is a good distance from the High Plains and significantly younger than Middle Archaic.

Francis and Loendorf (2002:113-114) investigated ethnographic accounts from the Shoshone Indians and tied them back to the petroglyphs and pictographs found along the Upper Wind River of Wyoming. The Upper Wind River is geographically close to where Don the ranch manager discovered the goose effigy and the two McKean Lanceolate points. Historical accounts from Shoshone Indians might seem a “bridge too far” when trying to tie their ethnography to a five-thousand-year-old goose with two Middle Archaic projectile points. I will play that hand anyway since it is the only hand I have to play. I will borrow an old geology axiom called Uniformitarianism which states that the “present is a key to the past.”

Francis and Loendorf reported an

abundance of flying and winged creatures represented on petroglyphs and pictographs

along the Upper Wind River. Bird-type creatures inspired the prehistoric artists’

imaginations. There are examples of a cannibalistic owl the Shoshone Indians call

wokai mumbic. That owl shook the earth and caused thunder when it

flew. There are members of the Shoshone tribe who still believe that owls predict evil. According

to Shoshone legend, a tiny hummingbird-like creature on the rock art symbolized a thunderbird and the eagles on the rock art could create lightning just by flapping their

wings. One bird type missing from the rock art was any type of waterfowl.

What intrigued the Middle Artisan sculptor into picking a goose as his subject? For one thing, migratory bird journeys are harrowing and unpredictable experiences. Geese survive those journeys by sticking together and helping one another. Gaggles of geese fly in a V-shaped formation or an echelon to conserve energy and increase the overall distance they can fly. When an individual goose flaps its wings, it creates an updraft which reduces the amount of energy used by the goose flying behind it. When flying in a V, energy conservation occurs throughout the gaggle for all geese except the lead goose. The lead position in the echelon is the most demanding. That is why gaggles share that responsibility among its members.

|

| Figure Eight - Profile shot of the goose effigy. The material appears to be claystone or limestone. |

The migration of waterfowl could have inspired our Middle Archaic artisan. Bird flight must have seemed quite magical five thousand years ago. The physics that explained bird flight was far in the future. Imagine trying to understand flight five thousand years ago without the knowledge we have today. Gaggles of geese flying high above in an orderly fashion while honking away must have appeared almost mystical.

In an analysis of spirit animals, Bobby Lake-Thom (1997:110-111) wrote that geese provided Native Americans an indication of the changing of seasons. Triggered by temperature, food supply, and sunlight, flocks of geese gather together to migrate south for the winter and then repeat the process when they return north in the spring. Waterfowl migrations could have signaled nomadic prehistoric humans to move on with the changing seasons.

Why did that Middle Archaic artisan select a goose as his

or her model? One theory might be that the goose effigy represented a spirit animal to a shaman or artisan. Still, questions remain. For example, what is the significance of the two nearly identical McKean Lanceolate projectile points

found with the goose effigy? And were the projectile points ever used or were all

three artifacts part of a shaman’s medicine pouch? We will never know for sure.

What are your thoughts?

|

| Figure Nine - Ventral view of goose effigy. |

References Cited

Cohen, Kenneth

2003 Honoring the Medicine: The Essential Guide to Native American Healing. Random House Inc. New York.Conard, Nicholas

2003a Palaeolithic ivory sculptures from southwestern Germany and the origins of figurative art. Nature, Vol 426, 18/25 December 2003.

1987 The Great Journey: The Peopling of Ancient America. Thames and Hudson Ltd. London.

2010 Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers of the High Plains and Rockies. Third Edition. Left Coast Press Inc. Walnut Creek.

1997 Spirits of the Earth. The Penguin Group. New York.

Museum of Native American History

2023 Duck Effigy Pipe. http://www.monah.org. Bentonville, AR.Mulloy, William

1954 The McKean Site in Northeastern Wyoming, published in Southwestern Journal of Anthropology, Volume 10, Number 4.Parman, Ray Jr.

1989 Rare and Unusual Artifacts. Fred Pruett Publishing. Boulder.Russell, Virgil Y.

1974 Indian Artifacts. Johnson Publishing Co. Boulder.

Steege, Louis C., and Warren W. Welsh

1968 Stone Artifacts of the Northwestern

Plains. Northwestern Plains Publishing Company. Colorado Springs.

Taylor, Jeb

2006 Projectile Points of the High Plains. Sheridan Books. Chelsea.Thomas, David Hurst

1994 Exploring Ancient Native America: An

Archaeological Guide. Macmillan Publishing. New York.

Warren, Robert E.

2007 Thunderbird Effigies from Plains Village Sites in Northern Great Plains in Plains Village Archaeology, edited by Stanley A. Ahler and Marvin Kay. Pp. 107-125. University of Utah Press. Salt Lake.

1978 Prehistoric Man on the Great Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman.

1952 A Note on the McKean Lanceolate Point. Plains Archaeological Newsletter, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 45-50.

John Bradford Branney is a geologist, prehistorian, and author. Born and raised in Wyoming, his grandfather's artifact collection drew him to his strong interest in prehistoric man at a very young age. Since then, he has found and documented thousands of prehistoric artifacts.

Branney has published twelve books and around one hundred articles on archaeology, geology, and his wandering. He resides in the Colorado mountains with his family.

.png)