|

| Figure One. Scottsbluff knife form from Wilson County, Texas. The most interesting feature of this, 10,000 years plus beauty, is its burinated tip. John Bradford Branney Collection. |

In the knapping process called burination, a small, relatively thick flake is removed from a flake, blade, or biface using a snapped termination or previous burination scar as the knapping platform. Burination can also be used to remove a sharp edge for the safe handholding of a knife form. Burination was extremely common in the “Old World” Paleolithic of Europe, Siberia, and Beringia. Paleoindians in North America also made and used burins. For some reason, it appears that the Clovis culture only used burination in rare instances, but it became quite popular during Folsom and Cody Complex times. Most of my stone tools with burins came from my Folsom and Cody Complex sites.

Figure one is a photograph of a 3.7 inch long Scottsbluff knife form, made from Edwards Chert and found on private land in Wilson County, Texas. This artifact is Early Archaic with an approximate age of 10,000 years. The knife form had two or three resharpenings that have reduced its overall length, but the most interesting feature of this Scottsbluff knife form is its tip (figure two). The tip of the knife form at some time was pressure flaked into a burin tip (an engraver) and was re-tipped two more times. Burination strengthened the tip of the Scottsbluff knife form exponentially, keeping the edge from crushing and failing while engraving hard objects.

Most burins and burin spalls are unspectacular features. Most people do not even recognize them. Caution has to be applied when differentiating an impact fracture from a burin. Not every missing sliver off an artifact is a burin! Finding impact fractures on an artifact is far more common. Usually, after I post artifacts with burins, I receive a rush of requests to look at people's artifacts who think they might have burins. Identifying burins from photographs is difficult at best. It is best to have the artifact in hand so that you can feel the edges for use wear and examine the artifact. All of my artifacts that I claim to have burins have gone through thorough examination and scrutiny.

|

| Figure Three. My heart was pounding! |

Figure three is an in situ photograph of a Scottsbluff (Cody Complex) point half-buried in the sandy creek bottom at my SHADOWS on the TRAIL site in northern Colorado. The day was August 23, 2008, when I spotted this Scottsbluff point lying in the sand. It took my breath away and my heart pitter-pattered. It was obvious what it was, but the tip was buried. The square base and the flaking pattern were definitely Cody Complex. After a somewhat extended photoshoot, I pulled the Scottsbluff point out of its sandy grave. My heart sank when I saw that an impact fracture had taken off the tip of the point.

|

| Figure Four. Scottsbluff point with a blunted tip. |

I yelled out the PG-13 version of "DRAT!". Quite frankly, even though I had found a tremendous artifact I was disappointed because of the broken tip. My first reaction was that this beautiful 2.8 inch-long Scottsbluff point ended its useful life by hitting bone or rock and fracturing its tip. I pocketed my find and went back to hunting for the rest of the day. It wasn't until I got home later that night and had a chance to study the point that I realized that the original Scottsbluff point was probably decommissioned because of an impact fracture and the creative Cody Complex knapper recommissioned the point into a stone tool by intentionally creating a double-sided burin for use in scraping wood and hides (figure five).

My interpretation of the history of this Scottsbluff point goes something like this; The maker of this Scottsbluff point used a dendritic jasper as the raw material. The dendritic jasper looks like some of what I find on the Hartville Uplift of Wyoming. The finished projectile point at some stage suffered damage to its tip. Instead of repairing the projectile point, the Cody Complex knapper refurbished the broken point into a knife form with double burins. He or she removed burin spalls on both sides of the impact fracture (figures five and six). Then the innovative knapper created a chisel-like edge on the rounded tip. He or she could have used this Scottsbluff knife form as a burin, knife, scraper, and chisel for use on meat, bone, wood, and hides.

|

| Figure Six. Chisel tip is well polished. |

The raw material at the tip of this Scottsbluff knife form has a different color and texture than the rest of the artifact. I attribute this to polish or use-wear from the way its owner used it. There is evidence that the owner might have re-tipped or repaired the chisel and burins once or twice since that area of the knife form has a different flaking pattern than the rest of the biface.

Another important feature about burins when found in Paleoindian contexts, they seldom show use wear on the edge near where the burin spall detached in front of the striking platform. Instead, use-wear is usually found on the edge adjacent to the striking platform or tip. In the case of this last Scottsbluff point, the most use wear was at or near the tip.

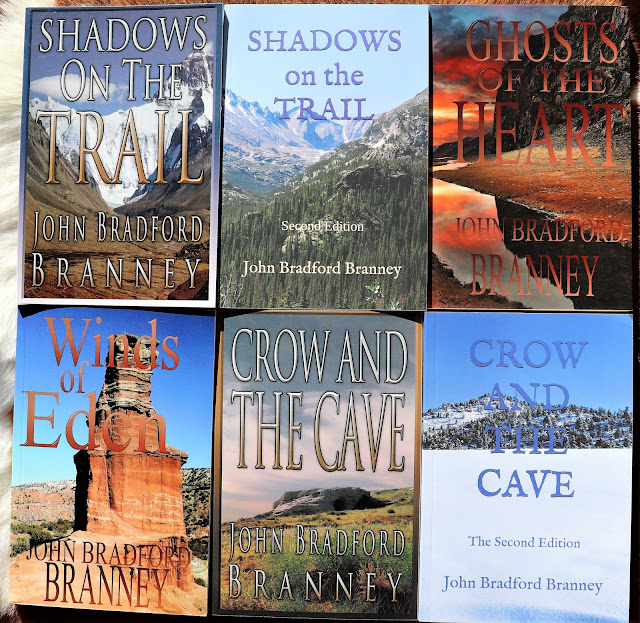

So, there you have it. A couple of Cody Complex burin examples. You will have to read the SHADOWS ON THE TRAIL Pentalogy to see how the Folsom Complex used burins. All the information needed to order your copies of my book series is below.

Don't miss out on a prehistoric adventure you will never forget!