Who Were Those Guys?

A Shadows on the Trail Adventure

by John Bradford Branney

|

Figure One - The red arrow indicates the location where I found a 1.8-inch-long

Washita arrow point. Prehistoric rockshelter in the background. |

The northeastern Colorado ranch is

located in a large bowl-shaped basin. A small intermittent creek drains the basin to the southeast. The creek is fed cool water from several natural springs along its route. The creek was quite prolific in the past,

meandering and braiding its way tens of miles until joining the South Platte

River. Over the last hundred years, agricultural use caused a few of the creek's water sources to dry up.

The headwaters of the creek butt up

against sandstone bluffs of the Oligocene-Miocene geological age. In the past, finding extinct

mammal fossils was as easy as pie; it is not so easy these days. It was also easy to find prehistoric artifacts a few decades back, but now I have to work for every artifact. In the past, I found chipping debris galore,

fire-blackened rocks eroding out of embankments, and several artifacts on any given day. Over the past forty years of hunting the ranch, I have discovered everything from Clovis to historical Indian artifacts and every prehistoric culture between. It would

be a shorter list for me to name the High Plains projectile point types I have not discovered on the ranch versus listing the projectile point types that I have discovered. But over the last decade, my artifact finds have dwindled. I

still hunt the ranch two or three times a year, and occasionally I land a nice artifact, but the glory days of artifact hunting are gone. However, I still have a few stories about artifact hunting on the ranch.

In September 2003, I returned to the

High Plains from my home in Texas to hunt artifacts. Originally, I was not scheduled to hunt the ranch because I wanted to let natural erosion catch up with my artifact-hunting pressure. However, I found an extra day in my schedule with nothing planned so I told myself, “Why not hunt that ranch?” And I am glad I did. I found a couple of beautiful end

scrapers, several broken projectile points, a mano, several other worked

pieces, and the "prize of the day." This story is about that "prize of the day" and the people who probably made it.

|

Figure Two - In situ photograph of the 1.8-inch-long

Washita arrow point. |

The "prize of the day" was a beautiful 1.8-inch-long Washita arrow point eroding from an embankment approximately twenty to thirty meters down the hill from the prehistoric rockshelter in Figure One. To this day, it is one of the finest Washita points that I have ever found (Figures Two and Three).

|

Figure Three - 1.8-inch-long Washita arrow point made

from what I believe is Smoky Hills Jasper out of Kansas. |

The prehistoric humans who made that projectile point used a raw material called jasper. Prehistoric people liked jasper, and based on this jasper's yellowish tone, the projectile point's raw material might be Smoky Hills Jasper out of Kansas but I cannot be sure.

Central Plains Tradition

From around A.D. 900 to A.D. 1000, the people of the Missouri

River areas of Kansas, Nebraska, and South Dakota, in what archaeologists call the Central Plains tradition, were influenced by the prolific Mississippian culture to the east. The people of the Central Plains tradition shared similar

technologies, subsistence patterns, and socio-economic systems across a wide geographical area. Archaeologists have traced the Arikara, Mandan, Pawnee, and other historical Indian tribes along the Missouri

River Basin to the Central Plains tradition.

The Republican River is a small

tributary of the Missouri River with its headwaters originating in eastern Colorado. The river flows from its headwaters in Colorado across northwestern Kansas into southwestern

Nebraska and then back into north central Kansas before joining with the Kansas

River, which ultimately joins the Missouri River.

The discovery by archaeologists of prehistoric hamlets

in central and eastern Nebraska and Kansas gave rise to a phase within the Central Plains tradition called Upper Republican (Strong 1934). Based on radiocarbon

dating, the Upper Republican phase began around A.D. 1000 and lasted until around A.D. 1400. There are various hypotheses as to what happened to the people of the Upper Republican phase but that topic is outside the scope of this article.

Horticulture, hunting, and gathering drove the Upper Republican economy and lifestyle. Archaeological evidence indicates that the Upper Republican people grew maize, gourds,

squash, beans, and sunflowers. They cultivated their crops with hoes made from

the scapula bones of bison. Evidence shows that the Upper Republican people on the Central Plains supplemented their farming and hunting with wild plant harvesting, fishing, and mussel gathering.

The Upper Republican phase on the Central Plains was characterized by substantial earth-lodge dwellings (Wedel 1961:94). The people lived in rectangular to semi-rectangular lodges built

slightly below the ground surface. The lodges ranged from 500 to 1200 square

feet with covered entrances facing south or east, away from the prevailing winter winds. A central fire pit

and one or more subterranean cache pits were located within each lodge. Posts outlined the perimeters of each lodge with four or more postholes found in the middle for roof

support. The lodges were randomly placed along mostly stream terraces and exhibited little or no central planning. (Steinacher and Carlson 1998).

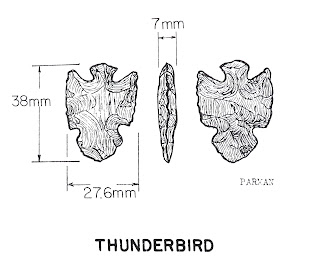

The main chipped stone tool

assemblages of the Upper Republican phase were associated with hunting,

butchering, and animal hide processing. Artifact assemblages included bifaces

of various sizes and shapes for cutting and chopping, end scrapers, engravers,

and drill forms. The projectile points associated with the Upper Republican

phase were usually small and triangular, with side-notches and tri-notches. When found on the High Plains, artifact hunters like myself classify those small triangular side-notched and

tri-notched projectile points as Washita and Harrell arrow points. Figure Four is a photograph of examples of Washita and Harrell arrow points that the author surface found in northeastern Colorado. The centerpiece is the Washita point photographed in Figures Two and Three.

|

Figure Four - Examples of side-notched and tri-notched arrow points surface

recovered on the High Plains of northeastern Colorado. The author assumes

these points originated in the High Plains Upper Republican phase.

Is that a good assumption? |

Upper Republican ground stone tools

included pipes, abraders, hammerstones, spheres, manos and metates, nutting

stones, and disks. Bone implements included bison scapula hoes, splinter awls,

eyed needles, fishhooks, beads, tubes, and shaft wrenches. Less dominant bone

tools included engraved bison bone toes, eagle bone whistles, and in one case

an engraved human skull fragment (Steinacher and Carlson 1998; Wedel 1986:108). I have found examples of some of those ground stone tool types on the High Plains but since other prehistoric cultures used them as well, I cannot attribute my surface finds to the Upper Republican phase.

|

| Figure Five - from Cassell (1997:214) |

A thinner-walled, globular ceramic pottery design from the Upper Republican phase replaced the thicker-walled, conoidal

ceramic pottery design from the earlier Plains Woodland tradition (Figure Five). According to Ellwood (2002:34), Upper

Republican people constructed ceramic pottery using a lump or patch accretion method. Then they finished by rolling a cord-wrapped, dowel-like instrument along

the surface to seal the junctures. Raw materials for the vessels consisted

of locally derived crushed sedimentary rock, clay, and granite. Upper Republican ceramic pottery was jar- to pot-sized and exhibited high shoulders with narrow necks and

collared or braced rim mouths (Wedel 1986:106).

The Upper Republican potters often decorated the collars with two to eight incised horizontal lines, repeated triangles,

or excised nodes. The surface finish exhibited short, choppy cord marks,

with obliteration or smoothing of the cord marks, especially near the

bottom of the pot. Handles or lugs were rare on Upper Republican ceramic pottery.

Wedel (1986) proposed that Upper Republican ceramic pottery might have been used to boil meat or vegetables, such as maize, beans, and wild tubers; or for dry storage; or as water containers. The Upper Republican ceramic pottery design from the Central Plains carried over onto High Plains sites which I discuss in the next section.

|

Figure Six - Upper Republican potsherds from eastern Colorado. Bottom row left

to right: Weld County, Lincoln County, Lincoln County. Top row: Weld County. |

Sigstad (1969:18-19) identified two classes of Upper Republican ceramic pottery. Class I Frontier Ware exhibited collared rims while Class II Cambridge Ware exhibited flared rims. Figure Six exhibits Upper Republican potsherds which I surface recovered on the High Plains. On July 6, 1986, I found the rim fragments in the center and right of the lower row. I discovered them near a north-facing rock shelter on private land near Cedar Point in eastern Colorado. Note the incised horizontal lines near the bottom of each fragment. Both pieces appear to have originated from the same ceramic pot. I recovered the other two rim fragments from multicultural sites in Weld County, Colorado. Those rim fragments fall within Sigstad’s Class II Cambridge Ware category also.

I have found hundreds of potsherds while surface hunting for artifacts in northeastern Colorado and southeastern Wyoming. The potsherds are usually small, measuring one inch by one inch or smaller. On that scale, it is nearly impossible for me to tell whether the potsherd originated from an Upper Republican or Plains Woodland ceramic pot. Identification of the culture is much easier if the potsherd is from a distinctive rim or is large enough to see the curvature of the original pot.

Elwood (2002:40) suggested Upper Republican and Plains Woodland ceramic pottery can be differentiated using form and surface finish. While Plains Woodland vessels were conoidal in shape, Upper Republican vessels were globular in shape (Figure Five). That only helps if the potsherds are large enough to determine the curvature of the original pot. Elwood stated that while Plains Woodland exhibited clear and deep cord marks, Upper Republican cord marks were often choppy, smoothed over, or partially obliterated. Figure Seven shows a few potsherds I found in northeastern Colorado. Note the clear and deep cord marks on most of the pieces. I believe all of the potsherds in the figure originated as Plains Woodland pottery except perhaps the bottom pieces on the left which could be Upper Republican.

|

Figure Seven - Surface found potsherds from northeastern Colorado.

Did these come from Plains Woodland or Upper Republican?

|

The High Plains Upper Republican Phase

At the same time that Upper Republican people were inhabiting small hamlets in central Kansas and Nebraska, a similar-aged culture existed along the grasslands of western Kansas and Nebraska, eastern Colorado, the panhandle of Nebraska, and southeastern Wyoming. I will refer to that similar-aged culture as High Plains Upper Republican even though I believe its relationship to the original Upper Republican phase on the Central Plains is unknown. Archaeological evidence suggests that High Plains Upper Republican people occupied sites along the escarpment ridge flanking the Colorado Piedmont, (Irwin and Irwin 1957; Wood 1967), the northern and southern tributaries of the South Platte River, and the Arikara-Republican drainage system (Withers 1954).

High Plains collectors and professionals discovered artifacts in rock shelters, on buttes and bluffs, and along stream terraces similar to those documented at the Upper Republican hamlets in central Kansas and Nebraska. The rock shelter sites were quite small and occupation zones consisted of diffused middens containing chipping debris, animal bone fragments, hearths, and ashy soil. The butte and bluff campsites offered excellent views but meant hauling water upslope and those sites did not offer protection from cold northerly winds.

Archaeologists investigated and documented several High Plains Upper Republican campsites in eastern Colorado including the Peavy, Smiley, Agate Bluff, and Happy Hollow rock shelters and the Buick, Kasper, Biggs, and Donovan open campsites. Radiocarbon dating suggested occupations between A.D. 1000 and A.D. 1400 (Wood 1990).

In comparing the original Upper Republican sites in central Kansas and Nebraska with the High Plains Upper Republican sites to the west, Laura L. Scheiber (2006:135) wrote, "These western sites are known more for what they lack (houses, hoes, and corn) than for what they possess." The Upper Republican people on the Central Plains held different lifestyles than those on the High Plains. To the east, the Upper Republican people placed heavy emphasis on horticulture and permanent dwellings while in the west there was little or no horticulture and permanent dwellings. Thus far, the only evidence of any horticulture for the High Plains sites was a single maize kernel buried four and a half feet deep at the Agate Bluff site in northeastern Colorado. Cassell (1997) also noted that bison scapula hoes, prominent on the Upper Republican sites on the Central Plains were completely absent on the High Plains sites. During my research, the closest I found for permanent dwellings on High Plains Upper Republican sites were the pit houses archaeologists investigated at Cedar Point Village (Wood 1971:55-56). Wood (1971:81) suggested that "Cedar Point pit houses are not comparable to any of the five-post foundation structures reported by Gunnerson for Dismal River."

Scheiber (2006:135) stated above what was missing from the High Plains sites, so what did the High Plains sites have in common with the original Upper Republican sites on the Central Plains? Based on radiocarbon dating, sites on the Central Plains and High Plains existed contemporaneously from around A.D. 1000 to A.D. 1400. Archaeologists have also identified the same styles of ceramic pottery and projectile points on the High Plains and Central Plains sites.

|

Figure Eight - Washita-lookalike arrow point surface recovered on

private land in southwestern Wyoming on 9/3/2013. I cataloged

this arrow point as a Plains Side-Notched. |

When I surface recover a Washita or Harrell projectile point in eastern Colorado or southeastern Wyoming, I assume the High Plains Upper Republican people made that point. Is that a good assumption? Probably not since I find Washita and Harrell lookalikes outside the known geographical range for High Plains Upper Republican. Figure Eight is such an example. I discovered that 1.1-inch long Washita lookalike point on September 3, 2013, on a private ranch west of Baggs in southwestern Wyoming. It looks like a Washita arrow point in every aspect but I found it well outside the geographical range for High Plains Upper Republican. In southwestern Wyoming, that type of projectile point is not called a Washita, it is called a Plains Side-Notched.

The side-notched point in Figure Eight is not an anomaly. I have found many Washita and Harrell lookalikes across the High Plains. Washita and Harrell point lookalikes are found all across Wyoming, Montana, and the Dakotas to the north, and as far south as Oklahoma and Texas. Similar point types are found in the Southwest and across the Great Plains. Collectors and archaeologists have christened them with names such as Plains Side-Notched, Plains Tri-Notched, Billings, Desert Sierra, Desert Delta, Reed, Peno, Cahokia, Irvine, and Emigrant, just to name a few.

Were those projectile point designs a convergent technology developed independently from the Upper Republican phase? Did those projectile point designs originate in the Central Plains and spread from there or did those designs originate someplace else? Does the lack of High Plains sites underestimate the geographical range of the Upper Republican phase? Were the Washita and Harrell projectile points I photographed in Figures Three and Four made by High Plains Upper Republican people? Those are unanswered questions I found no answers to during my research.

Of course, people have opinions, but opinions are only sometimes backed up with facts. Bottom line, side-notched and tri-notched projectile points like Washita and Harrell were widely used, far beyond the known range of High Plains Upper Republican. The design swept across the entire western part of the continent. Surface finding Washita and Harrell projectile point types in the geographical range for High Plains Upper Republican is still not conclusive evidence for the presence of High Plains Upper Republican.

|

Figure Nine - A small rockshelter I discovered in eastern Colorado in the 1980s.

The roof of the rockshelter collapsed a couple of decades ago, burying

the remaining prehistoric occupation levels under rocks. |

Figure nine was a small south-facing rockshelter I

discovered in eastern Colorado in the early 1980s. On my initial visit, I found ash, charcoal, burned bone, and chipping debris on the ground in and around the shelter. Most of the rockshelters I have investigated faced south. Facing south meant the rockshelter captured sun rays in the winter and the rock behind the rockshelter blocked those nasty winter winds. That particular rockshelter was small and could only accommodate a single family. The roof of the rockshelter looked unstable so I contacted a local university to see if they were interested in investigating it. The university never bothered to get back to me, so I proceeded with my salvage operation.

In that rockshelter, I found a lot of chipping debris and burned bone. I also found a couple of bone awls, several Late Prehistoric projectile points including Plains Woodland and

Upper Republican types, scrapers, and a couple of flake knives. On the pasture in front of the rockshelter, I discovered several Late Prehistoric and Late Archaic

artifacts. The roof collapsed on the rockshelter fifteen to twenty years ago, burying the remaining occupation levels under massive sandstone boulders.

Theories of Origin for High Plains Upper Republican

Any viable theory on the origin of High Plains Upper Republican must provide evidence that answers basic questions. Did earth-lodge dwellers from the Upper Republican phase of the Central Plains tradition abandon their earth-lodge homes and lifestyles and head west to the High Plains? If so, was that move to the High Plains seasonal or permanent? Or did indigenous people already living on the High Plains interface and trade with the original Upper Republican people from the Central Plains?

Lindsey and Krause (2007:96) encapsulated the wide range of theories by stating, "Ceramic-bearing campsites in eastern Colorado and western Nebraska have been attributed to Woodland stage hunters and gatherers, mobile hunting/gathering populations making Upper Republican-like pottery, and Upper Republican cultivators ranging to the west to hunt."

Wedel (1961:102) suggested that there was a need for more evidence to be collected and analyzed from the High Plains sites before questions of origin could be answered. He stated that it was impossible to determine whether Upper Republican material on the High Plains sites marked seasonal hunting camps for the Upper Republican horticulturists out of the Central Plains.

Wood (1969) proposed that the Upper Republican campsites on the High Plains were occupied by Upper Republican earth-lodge dwellers from the Central Plains during seasonal hunting forays. Wood's evidence was based on a lack of burial sites, horticultural tools, and permanent structures at the High Plains campsites. Wedel (1970:7-10) and Reher (1973:119) argued that Wood's theory was illogical. Reher refuted Wood's claim that earth-lodge dwellers would travel two hundred miles across excellent bison hunting grounds to hunt other bison on the High Plains.

By comparing artifact inventories reported from historical Pawnee hunting trips to the artifact assemblages in Upper Republican campsites on the High Plains, Roper (1990) argued that the artifact assemblages on the High Plains were too culturally diverse and well-represented to be from temporary hunting camps.

Steinacher and Carlson (1998:248) summarized three hypotheses for the High Plains Upper Republican sites. The first hypothesis was the Wood proposal above where earth-lodge dwellers from the east made periodic or seasonal trips to the High Plains to replenish their resources. The authors noted that raw material originating in the High Plains was used almost exclusively on stone tools discovered in some Upper Republican sites in Kansas and Nebraska. That raw material could only get to the Central Plains from the High Plains by trading or transporting it.

Using geochemical analysis, Roper et al (2007) determined that a few of the ceramic pots discovered in High Plains Upper Republican sites used clay from the Medicine Creek area of southern Nebraska. That was evidence that at least a few Upper Republican ceramic pots were transported from the Central Plains to the High Plains. The researchers also noted that during the excavation of House 5 in the Medicine Creek area of Nebraska investigators discovered a large quantity of Flattop Chalcedony from eastern Colorado. That provided evidence of raw material movement from the High Plains to the Central Plains during the Upper Republican phase.

The second hypothesis suggested by Steinacher and Carlson was that some people from the east gave up their sedentary horticultural lifestyles on the Central Plains and took up nomadic hunter and gatherer lifestyles on the High Plains. That is a logical hypothesis if we assume that some humans around A.D. 1000 were as adventurous as the pioneers who settled in the western United States in the 1800s. Humans have a desire to live their lives the way they want. Some people prefer a predictable lifestyle while other people like taking bigger risks. The High Plains Upper Republican people might have abandoned their farming hamlets along the tributaries of the Upper Republican River in Kansas and Nebraska to head west just like the pioneers of historical times did.

The third hypothesis that Steinacher and Carlson suggested was that indigenous people already occupying the High Plains established trade with the Upper Republican people in the east. We already know that Upper Republican people along the Central Plains ended up with raw material originating from the High Plains, and ceramic pottery from the Central Plains ended up in High Plains Upper Republican sites. Was that material shared between two groups from the same phase or two entirely different phases or societies?

|

Figure Ten - 1.1-inch-long Washita arrow point that the author found on

May 18, 2024, in Logan County, Colorado. Over the decades,

the author has found many Washita and Harrell

arrow points and potsherds in the area. |

Conclusions

Is it a good assumption that High Plains Upper Republican was the western

extension of the Upper Republican phase of the Central Plains?

Based on archaeological evidence, the Central Plains and High Plains people lived

vastly different lifestyles. On the Central Plains, horticulture was an important part

of the economy while on the High Plains horticulture appeared to play little or no

role. Even with the different lifestyles, there was a relationship between the High

Plains and Central Plains people during the Upper Republican phase. At High Plains

sites, archeologists found Upper Republican pottery manufactured with clay from

the Central Plains, and at Central Plains sites, archaeologists found raw material

originating on the High Plains. We know that the Upper Republican people from the

Central Plains and High Plains used the same styles of side-notched and tri-notched

projectile points.

That is clear-cut evidence that material moved between the Central Plains and High

Plains populations during the Upper Republican phase. However, the evidence of

material movement does not define the social relationship between two groups of

people. Were those people kinfolk or not related? Did the Upper Republican phase

on the Central Plains use the High Plains as outposts or for seasonal hunting trips? I

found no smoking guns or evidence that conclusively answered those questions.

When excavating a Late Prehistoric site on the High Plains, archaeologists have

three markers used to identify the presence of Upper Republican. First, the age should fall

between A.D. 1000 and A.D. 1400. Second, small, triangular side-notched and tri-notched projectile points should be in the artifact inventory. And most importantly,

the distinctive Upper Republican ceramic pottery must be present. If there is

evidence of horticulture (corn), working hoes made from bison scapula, and

permanent dwellings that is a bonus, even though Scheiber (2006:135) reminded us

that, "These western sites are known more for what they lack (houses, hoes, and

corn) than for what they possess."

Surface finds of Upper Republican material are an entirely different ball game. For

one thing, it is impossible to accurately date materials out of archaeological and

stratigraphic context. Secondly, the presence of side-notched and tri-notched arrow

points of the Washita and Harrell variety may or may not be associated with High

Plains Upper Republican. The most important artifact for determining the presence of High Plains Upper Republican is the distinctive ceramic pottery. Of course, the

potsherds must be large enough to differentiate them from earlier Plains Woodland

ceramic pottery. Of course, finding an entire High Plains Upper Republican pot

would be a surefire indicator. I have been searching for that well-preserved ceramic pot for decades. Unsuccessfully, I might add. Finding a well-preserved Upper

Republican ceramic pot is as rare as finding moose feathers.

References Cited

Cassell, E. S.

1997 The

Post-Archaic of Eastern Colorado. In The Archaeology of Colorado, pp.

215-219. Johnson Books. Boulder.

Cooper, Steven R. 2018 The Official Overstreet Indian Arrowheads Identification and Price Guide. Stevens Point, WI.

Ellwood, Priscilla B.

2002 Middle

Ceramic Period in Colorado. In Native American Ceramics of Eastern Colorado.

University of Colorado Museum. Boulder.

Irwin, Cynthia, and Henry Irwin

1957 The

Archaeology of the Agate Bluff Area. Plains Anthropologist 8:15-38.

Lindsey, Roche M., and Richard A. Krause

2007 Assessing Plains Village Mobility Patterns on the Central High Plains in Plains Village Archaeology, edited by Stanley A. Ahler and Marvin Kay.

Reher, Charles A.

1973 A

Survey of Ceramic Sites in Southeastern Wyoming. The Wyoming Archaeologist.

XVI, pp 1-2.

Roper, Donna C.

1990 Artifact

Assemblages Composition and the Hunting Camp Interpretation of High Plains

Upper Republican Sites. In Southwestern Lore,

56(4): pp. 1-19.

Roper, Donna C., Robert J. Hoard, Robert J. Speakman, Michael D. Glascock, and Anne Cobry DiCosola

2007 Source Analysis of Central Plains Tradition Pottery Using Neutron Activation Analysis: Feasibility and First Results. Plains Anthropologist, Vol. 52, No. 203 (August 2007), pp. 325-335.

Scheiber, Laura L.

2006 The Late Prehistoric on the High Plains of Western Kansas, High Plains Upper Republican and Dismal River in Archaeology of Kansas, edited by

Robert J. Hoard and William E. Banks. Lawrence, KS.

Steinacher, T. L., and G. F. Carlson

1998 The

Central Plains Tradition in Archaeology of the Great Plains, edited by

W. Raymond Wood. University Press of Kansas. Lawrence.

Strong, William Duncan

1934 An Introduction to Nebraska Archeology. Miscellaneous Collections 93(10): iii-323.

Wedel, Waldo R.

1961 Prehistoric Man on the Great Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. Norman.

1970 Some

observations on “Two House Sites in the Central Plains: An experiment in

Archaeology. Nebraska History 51(2) pp. 1-28.

1986 Central

Plains Prehistory: Holocene Environments and Cultural Change in the Republican

River Basin. University of Nebraska. Lincoln.

Withers, Arnold M.

1954 University

of Denver Archaeological Fieldwork. Southwestern Lore 19(4):1-3.

Wood, J. J.

1967 Archaeological

Investigations in Northeastern Colorado. Ph.D. dissertation. University of

Colorado, Boulder, University Microfilms, Ann Arbor.

Wood, W. Raymond

1969 Ethnographic

Reconstructions. In Two House Sites in the Central Plains: An Experiment in

Archaeology, edited by W. Raymond Wood, pp. 102-108. Memoir 6. Plains

Anthropologist.

1971 Pottery Sites Near Limon, Colorado in Southwestern Lore, Vol. 37, No. 3, December 1971.

1990 A

Query on Upper Republican Archaeology in Colorado. In Southwestern Lore,

56:3-7.

About the Author

John Bradford Branney began collecting and documenting prehistoric artifacts in Wyoming with his

family at the ripe old age of eight years old. He has amassed a prehistoric artifact collection numbering in the thousands. He has written

eleven historical fiction books and over ninety papers and articles about Paleoindians, prehistoric artifacts, and geology. The author holds a B.S.

degree in geology from the University of Wyoming and an MBA in finance from the

University of Colorado. He lives in the Colorado Mountains with his family.

.png)